President Trump signed Executive Order 14281, “Restoring Equality of Opportunity and Meritocracy on April 23, 2025”. The EO proclaims a policy goal of eliminating “the use of disparate-impact liability in all contexts to the maximum degree possible’”. Given the relatively long history of the application of disparate-impact theory on fair lending and particularly redlining it is unlikely that the Administration will be able to jettison the concept entirely. However, this may be an opportunity to clarify a vaguely and inconsistently defined but nevertheless important concept underlying the application of disparate-impact theory in redlining analysis, the concept of a “Reasonably Expected Market Area” or “REMA”.

What the REMA concept is and how it is determined are absolutely critical to redlining analysis because “statistically significant” results are predicated on comparisons to “peers” in any given market, aka “REMA”. Expand or contract the delineation of a market and you concomitantly change the peers and their performance in “the market”. Consequently, the REMA has a profound impact on the benchmarks against which a statistically significant finding is determined. Theoretically, the lender and its peers should exhibit activity that reflects competition on a “level playing field”, but the application of the REMA concept as applied under the Biden Administration can best be characterized as arbitrary and capricious.

It is imperative that the REMA not only be “reasonable” but that it reflects the true market which is the basis for evaluating potential redlining. A distorted or unreasonably defined market (REMA) results in meaningless and potentially misleading analysis.

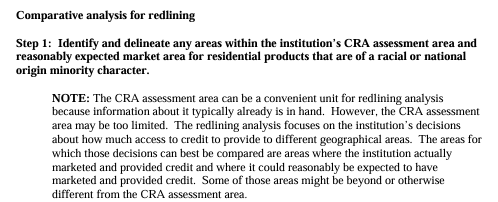

A major problem with the REMA concept is that it is not defined in law nor in regulations. It is simply a practice that appears to have been adopted by regulators without publicity sometime during 2009 for the purpose of redlining analysis. At that time the concept was first published in examiner compliance manuals (see Interagency Fair Lending Examination Procedures, August 2009).

It is shocking that such an important concept is so vaguely defined and left to the discretion of examiners, not the lender.

Nor are regulators required to be consistent in terms of the application of the concept. In fact, regulators adopted a radically different approach during the Biden Administration under the “Combatting Redlining Initiative” announced by Attorney General Merrick Garland in October 2021. Shortly after that press release, regulators announced that a REMA must consist of an entire MSA or MD or groups of counties within a statewide non-MSA. This contradicted REMA enforcement for the 12 prior years and violates the “reasonably be expected” standard that had been in effect since 2009. For many community banks this expansive definition of a REMA can only be described as a “UREMA” or “Unreasonably Expected Market Area”. Moreover, the aggregation of data over large market areas can create a statistical problem known as “Simpson’s Paradox” in which aggregated data can result in “statistically significant” results that are contradicted when the data is disaggregated based on submarkets within unrealistically large REMAs.

Statistical analysis can be affected by “Simpson’s Paradox” when the submarkets within a REMA are radically different. For example, in the Rochester NY MSA there are 6 counties (pre-2024 definition). All the active majority-minority tracts (“MMTs”) but 2 (that contain correctional institutes and exhibit no mortgage lending therefore) are in Monroe County. Consequently, if a community bank is based in the other counties in the MSA its mortgage lending patterns may give the appearance of redlining when the REMA embraces the entire MSA. But such an impression would be grossly misleading.

In fact, the New York Department of Financial Services explicitly acknowledged that possibility in its Second Report on the Department’s Inquiry into Redlining that states, “Consistently low percentages (of mortgages to minority borrowers) could suggest that scrutiny by regulators is warranted. However, as the Department noted in its 2021 Report, low percentages do not necessarily mean that the lender is engaged in discrimination or is violating fair lending laws. For example, some institutions may appear on these charges because they engage in lending in the broader MSA or county, but their seemingly poor performance in lending in MMTs (and to minorities) can be explained by the fact that their operational footprint is in rural areas outside Rochester or Syracuse, or in other areas where there is less opportunity for MMT and minority lending.” (pages 13-14).

The Trump Administration’s revisiting of the concept of “disparate impact” is a good opportunity to focus on redlining and the undefined REMA concept. While it is unlikely to overturn the legal application of disparate impact, the Administration can easily address the REMA problem by having regulators publish a definition of what a REMA is and how it is to be determined. Consistent with the definition of a CRA assessment area, a REMA should be limited to the area in which a lender can “reasonably be expected to serve.” In other words, the REMA should be consistent with how “reasonable” it is for a bank to serve considering a bank’s size and resources and its long-term marketing strategy as long as it not overtly avoiding underserved neighborhoods. This could go a long way preventing regulator abuse of a vaguely and inconsistently defined concept that can be manipulated to create a false impression of redlining.